Before tonight's absorbing Champions League Semi-Final match (Man Utd 1- 0 Barcelona, Hurrah!) on ITV, the final ad break was taken up entirely by one single commercial. An awesome commercial. If you like football, you'll probably like the advert - its thrilling, brilliantly shot and even quite funny, especially in the appearance of Marco Materazzi.

I instantly wondered who had directed it. Somebody young and hip, at the cutting edge of cinema, perhaps? Well, no actually, it was Guy Ritchie. I hate his films, but that is based mostly on his inability to write a single believable line of dialogue or create an interesting, convincing character. Visually, he has always been assured behind a camera. His films are all slickly put together with a control and feel for the surface of things - for colour and visual tone and atmosphere - which seems perfectly suited to advertising.

For this advert, he seems to have tapped into a style which has been conspicuous in Pop culture over the last year or so - the first person POV. "Cloverfield" and "[Rec]" have both used this device with a degree of success in the context of horror stories over the last few months, and "The Diving Bell & the Butterfly" used it to heartwrenchingly emotional effect. But what Ritchie's advert (entitled "Take It to the Next Level") is really reminiscent of, especially in its non-football scenes and its vomiting shot, is the briefly infamous video for the Prodigy's "Smack My Bitch Up". It also recalls, to an extent, the Michael Mann Gridiron advert I posted here last year, in its relentless motion and the procession of superstars it parades fleetingly before our eyes. The song is "Don't Speak" by the Eagles of Death Metal. It becomes instantly the best thing Ritchie's ever done:

Showing posts with label man utd. Show all posts

Showing posts with label man utd. Show all posts

Wednesday, April 30, 2008

Wednesday, October 10, 2007

Roy Keane

"Going to work was like going to War."

21st April 1999, Stadio Delle Alpi, Turin - 11 minutes into the Second leg of the semi-final of their Champions League tie with Juventus, Manchester United were 2-0 down and seemingly out of the competition. Two weeks earlier, Juventus had dominated Utd at Old Trafford in the first leg and been unfortunate to concede a last minute Ryan Giggs goal which kept the English team in the tie. And this was a seasoned Juventus side, with the experience and power of Conte, Davids and Deschamps alongside the skill of Zidane and Pessotto. The notion of getting a result against them at home was an unlikely one, made even moreso by the 2 goal deficit. Inzaghi had scored both of the goals, the first a piece of classic poaching from Zidane's cross, the second taking a wicked deflection off Jaap Stam. There was the suspicion that this Juve team had the measure of Utd. They had crossed paths a few times over the previous five years and Juve had generally emerged on top, a rollicking 3-2 defeat at Old Trafford in 1997 apart. But in this game, Roy Keane seemed to will his team to win. Provided with the aggressive, terrier-like Nicky Butt as his midfield partner, Keane never gave the Juventus midfielders an inch or a second on the ball, hustling and cracking into tackles. Zidane lost some of his composure, Davids seemed to lose some of his bottle. In his autobiography, Keane talks about knowing that Juventus weren't really up for the battle the way his Utd were and about going into a 50-50 with Davids, the Hard man of the Turin side. No contest, he says. Juventus were beaten, they just didn't know it yet. With Butt doing more of the dirty work than the more artistic Scholes usually did, Keane was the chief playmaker on that night, and his passing, when he was on his game, was almost hypnotically consistent. He played simple balls, but in all directions, of all types, long and short, lofted and rolling. He never stopped moving, open for the returned pass. He shouted and cajoled ferociously, driving his team on. He would not lose, you felt. He rose to nod in the first Utd goal and his determined celebration said it all - he knew there was more to come. Even when a late tackle on Zidane meant that he was booked and knew he would miss out on the final, should Utd reach it, he remained focused and driven. A goal from Yorke in the 34th minute meant that Utd were winning on away goals, and Andy Cole sealed the win in the 84th. The team were applauded off the pitch by Juventus fans. Alex Ferguson spoke of his Captain's performance in his autobiography : "It was the most emphatic display of selflessness I have seen on a football field. Pounding over every blade of grass, competing as if he would rather die of exhaustion than lose he inspired all around him. I felt it was an honour to be associated with such a player."

Performances like that one are the reason many Utd fans of a certain age love Keane more than any other player, more even than Eric Cantona. He gave the sense of truly caring in a way so many players manifestly do not - he seemed to care to an almost insane extent. Hence the outbursts, the snarling, the fighting. He was a supreme competitor, or as he himself put it: "the robot, the madman, the winner". Nowhere near as gifted as many of his peers in the battleground of midfield in World Football in the 1990s, Keane was a greater player than most of them because of his intelligence, but also because of his desire, his spirit and that aura.

He was a small boy, which made his breakthrough into professional football more difficult. His aggressive, competitive nature must have helped, and after a few failed trials, he eventually played in the Football League of Ireland for Cobh Ramblers, a smalltown club from Cork. There a scout from Nottingham Forest spotted him, and Keane signed for £47,000 in 1990. He quickly broke into the first team, making his debut and excelling against Liverpool at Anfield. He established himself as a starter at the expense of England International Steve Hodge and received his first call up to the Irish Squad. Back then, his style was very different. He was a goalscoring midfielder, with the happy knack of bursting late into the box to smack in a cut-back or a rebound. His game changed considerably after a few years at Man Utd, where he had moved for a then-record £3.75million in 1993. He became a more rounded midfielder, his prodigious energy and workrate making him a truly box-to-box player, both destroyer and creator. Initially he played alongside two players he superficially resembled - Bryan Robson and Paul Ince. But he would come to replace both at the heart of the team. Robson advised him to work on his defending and Keane did so, altering his game and allowing that fantastic engine to carry him into a ceaseless stream of tackles, blocks and interceptions. His reputation, both as a troublemaker and a player, grew. There were high profile red cards for late tackles, and for stamping on Gareth Southgate. His charisma and the fact that he was already becoming the team's new leader meant that he was a great story for the media. He badly injured himself stretching to tackle - to foul - Alf-Inge Haland in a game against Leeds, and missed most of a Season in which his importance to Utd was underlined by the team's lack of success. His return coincided with that Treble Season. But he attracted controversy, in his interviews, in his actions upon the pitch. He swung a punch at Alan Shearer. He led a pack of baying players after a referee to protest a decision. He criticised fans at Old Trafford. He refused to sign a new contract until he was given what he felt he was worth. He brutally, deliberatly fouled Haland in an act of vengeance he was then open about in his autobiography. He spent a night in a cell after a tabloid sting when the team were out celebrating in Manchester led to him becoming involved in an altercation with two women. He criticised the lifestyles and motivation of several teammates. He elbowed Jason McAteer in the face. The media, obviously, loved him.

His record at Man Utd only needs recounting. He played 326 games for the club, scoring 33 goals. He won more or less every available major trophy with the club, including a European Cup, 7 League titles, 4 FA Cups and 1 Intercontinental Cup. He played in 7 FA Cup finals, a record. In 2000, he won both Players and Football Writers Player of the Year awards. He was the only Irish player in Pele's 100 Greatest Living Players list. He was, quite easily, the dominant player of his era in the Premiership.

Perhaps his chief rival for that accolade is Patrick Vieira, his direct opponent at Arsenal. In Keane's time at Man Utd, Arsenal were almost always the closest threat, and his contests with Vieira were invariably central to the success or failure of the teams. Vieira was a better player in purely technical terms, with a great touch and those long telescopic legs enabling him to make some unbelievable tackles, plus a good range of passing and the ability to dribble skillfully. He could dominate an opposition midfield as well as anyone in the game...except Keane. He did not have quite as big an aura, quite as intimidating a presence. When he first emerged as a young player at Arsenal in tandem in midfield with Emmanuel Petit, Keane seemed unprepared for the challenge. But that didn't last long. Keane, as usual, compensated for his technical shortcomings with his will, his intelligence, his charisma, his ability to work harder than anybody else. He seemed to take Vieira's measure over his first few Seasons in England, and after that, Keane generally emerged the victor in their personal duels, just as he did with the emergence of Stephen Gerrard a few years later. Alex Ferguson once commented that Keane needed it to be a personal battle to thrive. He loved the personal combat, you vs. me, it was what brought the best out in him, and as such, he must have relished every meeting with Vieira. Keane probably peaked either in Utd's 6-1 demolition of Arsenal at Old Trafford in 2000 or when he scored both goals in a 2-0 win at Highbury. In the "Battle of Old Trafford" in 2004 when Arsenal players were confronting and baiting Utd players all over the pitch, none dared to approach Keane, not even Vieira, who Keane had shepherded off the pitch after his red card in that match, sparing the Frenchman further trouble. However, the climax of their rivalry came in the tunnel at Highbury in 2005, when Vieira threatened to "break Gary Neville's legs". Keane rushed to defend his teammate by haranguing Vieira about his own lack of qualities, asking him why he wasn't playing for Real Madrid and a few other comments (which Graham Poll, in his autobiography, says were amusingly witty and left Vieira threatening to break Keane's legs too) and ending the exchange with "I'll see you out there" as he pointed to the pitch. If that was some sort of attempted psyche-out by the Frenchman, it backfired, as Keane kept the ball, dominated the game and led Utd to a 2-4 win.

"It disappoints me that I didn't win the World Cup. People say 'but Roy, you played for Ireland, you were never going to win the World Cup'. I never saw it like that."

August 2001, Lansdowne Road, Dublin - Ireland need a result against Holland to qualify for the play-offs for the 2002 World Cup in Japan and Korea. They have, as usual, been drawn in a horrible group with a couple of Europe's modern heavyweights - the Dutch and the Portugal of the golden generation of Figo, Rui Costa and Couto. With Keane near the peak of his powers, the Irish have fought their way to some impressive results - drawing 2-2 with Holland in Amsterdam and drawing twice with the Portugeuse. Portugal will qualify automatically as group winners, and the winner of Ireland-Holland will take second place. Holland's squad is absolutely star-studded with an especially impressive array of strikers including Ruud van Nistelrooy, Pierre van Hoojdonk, Patrick Kluivert, Roy Makaay and Jimmy Floyd Hasselbaink. Most of them will be on the pitch by the end of the match as the Dutch desperately search for a goal. By contrast and with the exception of Shay Given in goal and Robbie Keane and Damian Duff up front, the Irish team is full of journeymen, average players who add to the collective. In such company, Keane's qualities become almost exaggerated in their importance. He is forced to prove his stature, to stamp his greatness on the game. He does it, seemingly, through sheer force of will. In perhaps the first minute of the match, Marc Overmars takes possession of the ball. Overmars is one of Holland's flair players, a dagger along the wing, with lovely touch, great pace and an eye for goal. He takes a touch with the assurance and confidence typical of a cultured Dutch player, in no hurry, aware of his space and his options. But one of Keane's best qualities has always been his hunger for the ball and his speed in making up ground in pursuit of it, and he is upon Overmars in an instant. His tackle is typically shattering, from behind, and though he gets the ball, he also takes plenty of the man. Overmars gets up looking shaken with Keane telling him not to make such a meal of it, and from then on, none of the Dutch midfield ever looks confident on the ball again. Mark Van Bommel tries to fight Keane's fire with his own, but finds that in such a war of attrition, few can match the Irish Captain (dutch Coach Louis van Gaal would vote for Keane as his European player of the Year in that Season, so impressed was he). Despite having Gary Kelly sent off in the 58th minute, Ireland win 1-0 courtesy of a Jason McAteer goal, with Keane dominant in the centre of the pitch. Indeed, his tackle and run began the move leading to that goal:

To truly understand just how good a player Keane was, his performances with Ireland have to be considered. For most of his International career, he found himself surrounded by players far inferior to his clubmates. Yet this appeared to inspire him. He drove them on just as remorselessly as he did the Utd team, if not moreso. One Dublin Newspaper regularly ran an alternative set of player ratings after every Irish match based around how many times Keane had shouted at the players. Hence the player shouted at the least had been Ireland's best player, Keane apart. And he was invariably Ireland's best player. This explains the impact his departure from the Squad at the World Cup in 2002 had in Ireland, where it was a socially divisive issue, mentioned in Parliament and omniprescient in the media for weeks. As David Walsh has written, Keane suffered from the burden of being the greatest player produced by a small nation. This meant that he became something of a champion in the Greek Warrior sense of the word. Ireland regularly played teams from bigger, stronger countries. These teams were often manifestly superior to the Irish team. But the Irish could ask any team in the World: who is your best player? This chap? Ok. Well, here is our best player. Now our best player will play your best player off the pitch. Just watch.

And Keane did it, time and again. Faced with Luis Figo, one of the most skillful players of his generation, Keane matched Figo's goal with one of his own and stymied the Portugeuse over and over. In a qualifier for the 2006 World Cup against France at Lansdowne Road, Keane dominated a French midfield made up of Zidane, Vieira, Makelele and Dhorasoo. It is inconceivable that Ireland would have limped out of that World cup in 2002 against Spain if Keane had been on the pitch. He would not have allowed it, not in such a manner, at any rate. But he was not on the pitch. His departure from the Squad was farcical, but just adds to his legend, in its way. It deprived him of his best chance to win that elusive World Cup, but has provided the raw material for two seperate plays and a couple of books: "Roy Keane's 10-minute oration ... was clinical, fierce, earth-shattering to the person on the end of it and it ultimately caused a huge controversy in Irish society." - Niall Quinn

That "oration" is part of what made Keane such a great player. There is a sense that he was almost waiting for the opportunity, that these complaints and criticisms he had harboured were a burden for him and he was almost glad to be rid of them. His wit and sharp tongue flashed occasionally in his interviews, but the snatches of that attack of Mick McCarthy revealed by other members of the Irish squad were both funny and cutting. Keane gave McCarthy no option but to send him home. The entire episode recalls the story told by Tony Cascarino in his book, of the entire Irish team kept waiting on a coach in Florida for Keane, young and relatively new to the squad, who has spent the night and morning in a local bar. Keane eventually arrived wearing a "Kiss me Quick" hat and was confronted by a furious Jack Charlton. "I didn't ask you to wait for me, did I?" Keane replied, stunning the older players, each of whom was petrified of their coach. When McCarthy, then Squad Captain and Senior pro, stepped in, his comment : "Call yourself a professional?" was met by Keane's "Call what you have a first touch?" What happened in 2002 really began on that day, according to Keane. His refusal to accept Ireland's second best status was the real sticking point, however. Ireland is a nation that celebrates reaching the Quarter Finals of a major competition, or at least it used to. Keane's attitude has changed that somehow, his reluctance to celebrate a draw with a great team when he knew Ireland could have won has spread through the culture alongside the great and unprecedented prosperity brought by the EU.

He always seemed to burn with some sort of fury - you could see it in his eyes in certain games, you could feel it in the way he terrified not just the opposition but his own teammates, too. He was a warrior. He laid it all on the line, left everything on the pitch, and he expected no less from those he played with. Thus his book and interviews are full of respect for those he considers proper professionals - the likes of Paul Scholes and Eric Cantona. But plenty of others he is less kind about. He might acknowledge somebody's talen while burying them in terms of personality. Peter Schmeicel played up to the crowd too much. Teddy Sheringham was a typical cocky, flash London wide-boy. He once claimed to have lost track of who he was not speaking to in the Utd dressing room. There are tales of him knocking out the big Danish goalkeeper in a training ground row, a sort of turf war, soon after Keane arrived at the club. Also the story that the famous Beckham "boot-gate" scar was in fact caused by the fist of Keane rather than a boot kicked by Fergie. Tellingly though, few who played with him at United have anything negative to say about him. Sheringham called him the best player he ever played with, as did Ruud van Nistelrooy. Few players share his warrior mentality, and it makes an impression on more sensitive teammates. It has carried him through his first year in Club Management at Sunderland, where he has also displayed his dark wit and acute intelligence in his interviews.

Footballers, whether they know it or not, are ambassadors. For clubs, for countries and for themselves. For decades, Mancunians knew that when they told foreigners where they were from, they would receive "Ahhh - Best, Law, Charlton" in return. Mention Brazil to so many people and they will instantly think of football. Argentina means Maradona. Liverpool might instantly summon the Beatles to mind, but after that its football. Roy Keane is possibly the only footballer from the Republic of Ireland with any kind of similar recognition factor worldwide. I've had personal experience of this which I found strangely touching, when I was in a little shop in the Argentine Andes a few years ago. The proprietor, a little old man, asked where I was from. "Ireland", I replied.

"Ah." he said. "Roy Keane. Very good player."

Monday, April 2, 2007

Paul McGrath

On 11 June, in the first game of the Italy 1990 World Cup Finals for either country, England played the Republic of Ireland in Cagliari. The game was terrible, like an English Second division match. The players all knew one another too well, their systems and styles cancelled each other out, and both teams were petrified of losing in what looked like being a very tight group. England took the lead with a Gary Lineker goal - the usual tap-in - before Kevin Sheedy equalised with a drive from the edge of the box. Both teams looked like they were content with a draw. The Italian press hated the match and described it as the worst they had seen so far at the finals, with the standard of football shamefully unimaginitive and primitive (Ireland would go on to play a worse game against Egypt a few days later). Both teams would qualify for the last 16, but neither played well in that group stage. Indeed, only two players really stood out at all from either team :Paul Gascoine for England and Paul McGrath for Ireland.

Paul McGrath is a legend in Ireland. As Footballers go, only Roy Keane really compares in terms of public affection. The Irish crowd chant of "Ooh-Ah Paul McGrath" (which Man Utd fans converted to Ooh-Ah Cantona) was best used when Nelson Mandela visited Dublin in the 1990s, only to be greeted with chants of "Ooh-Ah Paul McGrath's Da". The Irish chat show "The Late Late Show", the worlds longest running chat show, devoted one of its weekly programmes entirely to a review of McGrath's career, with appearances by most of the major figures in Irish football history. He has featured on an Irish stamp. I feel like even all these facts don't adequately convey just how worshipped he is. Given the meagre accomplishments in his club career, especially in comparison to other Ireland legends like Keane, Liam Brady, Johnny Giles or even Damien Duff, this may seem strange. But McGrath is probably the greatest defender ever to wear an Ireland shirt, and one of the handful of best players the country has ever had. The Irish football public knew class when it saw it, especially in the 1990s, when much of our football was effective but not especially classy. The way Paul McGrath played football was always classy.

Especially considering the way he lived his life. A functioning alcoholic for much of his career, in his autobiography he describes suicide attempts, black-outs, going AWOL while on Pre-season tours and playing many games drunk. He went missing a couple of times when he should have been playing for Ireland in impotant qualifiers, turning up in small hotels then fleeing from the media. All this only made him more popular in Ireland, where people love a flawed hero. McGrath is obviously a troubled man, and his vulnerability makes it easier to like him. Not only his evident self-destructive streak, but his chronic shyness and the way that he played the last decade of his career plagued with a succession of serious knee injuries only made him seem more heroic. As does his background - the child of an Irishwoman and Nigerian, he was given up for adoption as an infant and spent much of his childhood in a series of Dublin orphanages. Ireland was not remotely multi-cultural until this century, and it must have been difficult to grow up in the 1960s and 70s, mixed-race in working class Dublin. Football would have been a good escape, especially to somebody so naturally athletic and gifted. His first professional club were St Patricks Athletic, where he drew the attention of several English clubs and earned the nickname "The Black Pearl of Inchicore". Manchester United signed him in 1982, and he joined a side with a few Irish players already established, notably Frank Stapleton and Kevin Moran. This eased the shy McGrath's social acceptance, and he gradually eased himself into the first team of a talented United squad.

But it was a United squad destined never to win the biggest prizes. Many blame that fact on the incredible drinking culture at the club at the time. The team was the best in England on its day - routinely beating the dominant Liverpool team of the era - but inconsistent and often appallingly sloppy. Players like McGrath, Moran, Norman Whiteside, Brian Robson and Gordon McQueen would go on marathon midweek benders involving lock-ins and endless pub-crawling. Manager Ron Atkinson turned a blind eye, in the main. And there was some success - that United side won the FA Cup in 1983 and 1985. The Cup Final in 1985 was possibly McGrath's finest hour in a United shirt. Playing an Everton team that was probably the best in Europe at the time, winners of the League and the Cup Winners Cup, United went down to 10 men when McGrath's partner in central defence, Moran, was sent off for a lunging tackle on Peter Reid in the second half. McGrath later said that he partly blamed himself for that, since it was his poor pass that had presented Reid with the ball. He more than redeemed himself in the game, utterly dominating Everton's forward pairing of Andy Gray and Graham Sharp for the rest of the match. McGrath's principal gift was his great ability to read a game. On his good days he seemed to glide around the pitch, never rushed or stressed, always ahead of his opponents, nipping in to steal the ball off a toe, timing his leaps perfectly, always playing simple balls out of defence. He was strong and fast and agile, too, meaning that he could dominate any kind of centre-forward, from a nippy ball technician to a monstrous bruiser. That day he dominated two of them, always first to the ball, never caught out, ever alert and sharp.

Alex Ferguson was less forgiving of that United teams drinking culture, and he quickly broke it up, getting rid of Whiteside and selling McGrath to Aston Villa in 1989. He later said that McGrath was perhaps the most naturally gifted player he had ever managed, which is obviously the highest of praise. After a shaky start, Mcgrath went on to become Villa's bedrock player under first manager Graham Taylor, then Josef Venglos, until he was finally reunited with Atkinson. That Villa team came close to winning the League on a couple of occasions, finishing second behind United in 1993. McGrath was the Fan-favourite, nicknamed "God", and impressed his fellow professionals so much that he was voted Players Player of the Year in the same year. He would go on playing club football at the likes of Derby and Sheffield United until he was 37 years old and had undergone eight separate knee operations. From his first year at Villa he didn't train with the rest of the team because his fragile knees couldn't take the strain. Instead, he did an hour a week on an exercise bike. And yet his performance levels never really seemed to suffer. He got better with age and experience as his understanding of the game developed.

Part of his high standing in Ireland comes from having been a major player during the years of the National Teams greatest success. He played in the 1988 European Championships and the 1990 and 1994 World Cup finals. He excelled in each tournament, in fact. Coach Jack Charlton took his lead from previous manager Eoin Hand by playing McGrath in midfield at first. Ireland had a surfeit of quality centre backs during that era with Moran, David O'Leary, Mark Lawrenson and Mick McCarthy all in contention alongside McGrath. But McGrath had a combination of physical presence and ease upon the ball none of them could really match and so he found himself deployed as a holding player. He excelled there, too, neutralising the threat offered by Ruud Guillit in 1988. By 1994 he had established a new partnership at centre back with Phil Babb, while Roy Keane and Andy Townsend bossed midfield. In the first game of that tournament, Ireland faced Italy in Giants Stadium in New York. Italy, with players like Roberto Baggio, Beppe Signori, Paolo Maldini and Franco Baresi in their squad, were one of the tournament favourites. The game at Giants Stadium was expected to be like a home match for the Italians, with the great Italian community of New Jersey coming out to support them. Instead the stadium was filled with Irish supporters and Ireland fought out a 1-0 victory.

McGrath, whose left arm was paralysed by a virus throughout the match, was as poised and indominatable as ever. In his book he describes the way a match builds up a rhythm of its own, the way a forward and defender can both feel it. In that match, he says, Baggio, probably the best player in the world at the time, knew McGrath had the better of him, and he kept his distance. In that tournament, Ireland peaked in that, their very first match. All that remained were mediocre performances in the sweltering heat of midday games in Orlando in high summer and a desultory exit to Holland. McGrath was ushered out of the squad by new manager Mick McCarthy a few years later, nearing his late 30s, his knees in worse condition than ever. By then Ireland had a new talisman in Roy Keane, the heir to McGrath's crown as the teams only indisputably World-Class player. Keane gave Irish fans that feeling of safety that McGrath had done. With one of them in the team, there was always a strange feeling of security,as if they wouldn't alow us to lose, as if we knew that they would improve the standards of their frequently average colleagues. Generally they did. And never moreso than McGrath against Italy that day in New York.

Its just a pity that his catalogue of injuries and alcoholism conspired to deny him a fitting historical status outside Ireland. In 1987 he played at Wembley in a Centenary Game for a Football League XI against a Rest of the World XI that was like something from Pro-Evo* and looked totally at home. He was reckoned by many to be man of the match and comfortably subdued that terrifying attacking line-up.

There aren't any videos of him playing on the internet - I suppose great tackles, defensive headers and interceptions aren't as popular as goals and stepovers - but this is an excerpt from an Irish documentary about the 1994 World cup that gives you an idea :

* Football League XI : 1-Peter Shilton, 2-Richard Gough,3-Kenny Sansom, 4-John McClelland, 5-Paul McGrath, 6-Liam Brady, 7-Bryan Robson, 8-Neil Webb, 9-Clive Allen, 10-Peter Beardsley, 11-Chris Waddle.

Subs: Steve Ogrizovic, Steve Clarke, Pat Nevin, Osvaldo Ardiles, Norman Whiteside, Alan Smith, Selector: Bobby Robson,

Rest of World XI : 1-Rinat Dasaev, U.S.S.R.; 2-Josimar, Brazil; 3-Celso, Portugal; 4-Julio Alberto, Spain; 5-Glenn Hysen, Sweden; 6-Salvatori Bagni, Italy; 7-Thomas Berthold, West Germany; 8-Gary Lineker, England; 9-Michel Platini, France; 10-Maradona, Argentina; 11-Paulo Futre, Portugal.

Subs: 18-Andoni Zubizarreta, Spain, 12-Lajos Detari, Hungary, 17-Dragan Stojkovic, Yugoslavia, 13-Igor Belanov, U.S.S.R., 15-Preben Elkjær Larsen, Denmark, 14-Lars Larsson, Sweden, 16-Alexandre Zavarov, U.S.S.R. Selector: Terry Venables, England.

The Football League XI won 3-0 with two goals by Robson and one by Whiteside.

Wednesday, March 7, 2007

Juan Sebastian Veron

If you've read any of my other football posts, it'll be evident that I have a thing about playmakers. Number 10s. But then what fan of beautiful football doesn't? But there are other kinds of playmakers. Number 10s generally play in the "hole" position between midfield and attack in order to give the opposition the biggest problems. In the hole, neither the opposition's defence or midfield is sure whether they should be marking him. In the modern game, the best playmakers are either man-marked or the responsibility of a holding midfielder. But there is another sort of playmaker, one who plays further back up the pitch, in a more conventional central midfield position, and dictates passing from there. The midfield general, I suppose, though thats a phrase you don't hear so much anymore. Its almost a quarterback role, really, best-suited to players who can deliver high quality long passes to forwards in a split second. Perhaps the most successful example in the modern European game is Andreas Pirlo at AC Milan. Pirlo plays in a position normally associated with defensive midfielders, yet his tackling and covering abilities are limited at best. His passing, on the other hand, his ability to deliver a perfectly weighted through-ball to a sprinting Kaka or Gilardino on the edge of the opponents box from the half-way line, is exceptional. His ability to dictate play through his slide-rule passing is such that one of his nicknames in Italy is "metronomo". But, until last year there was another player in Serie A with a greater range of passing than Pirlo, a more sublime touch, more acute vision. That player was Juan Sebastian Veron.

Like Juan Roman Riquelme, Veron is a controversial figure in Argentine football. Like Riquelme, he was made the scapegoat for the failure of a talented Argentina squad to win a World Cup. But hes a very different player. Elegant and athletic, he covers ground effortlessly. Indeed, football seems almost too easy for Veron, which is perhaps why he has had image problems with fans. He never seems to be trying too hard, trusting instead in his athleticism and his brilliant technique. The fact that he is traditionally paired with a more obviously load-bearing or water-carrying player - Diego Simeone being the supreme example - only makes Veron look lazier and less commited by comparison. But his technique is his greatest strength. While he played for Manchester United, he and David Beckham played out an amazing warm-up routine before every game. They would take up positions on opposite touchlines and stroke the ball across the pitch in long sweeping arcs to one another, neither ever having to move even a step to receive the others pass. It served as a way for each to find his range. Once Veron's range was found, he was capable of punishing any opposition with a series of searching passes between defenders. Observe this volleyed pass, first time, to a breaking Beckham (whose finish isn't bad, either) :

Veron's father, Juan Ramon Veron, was a striker for Argentina and Estudiantes, nicknamed La Bruja, the Witch, which is where Seba's nickname La Brujita (little witch) comes from. He was renowned for his fine technique, another thing his son obviously inherited from him. Veron Jr began his career at his father's old club, Estudiantes, before moving on to Boca Juniors, where he played alongside the likes of Maradona, Claudio Caniggia and Kily Gonzalez. He only played 17 games for Boca in 1996 before he was brought to Europe, another in a long line of young Argentinians poached by big Italian and Spanish clubs. He spent 2 seasons with Sven Goran Eriksson's Sampdoria in Italy, breaking into the Argentina team and playing in the 1998 World Cup, where his deliberate style and ability to dictate the pace and direction of play from a deep position was perfectly suited to coach Daniel Passarella's cautious, defensive style. After the World Cup, Eriksson again bought Veron, this time spending £15million to bring him to Parma. That Parma team - with Lilian Thuram at the back and Hernan Crespo scoring plenty of goals from Veron's assists - won the Italian Cup in 1999. But Eriksson had already left for Lazio, and he soon lured Veron and Crespo to the same club, paying £18.1 million for the former and £35 million for the latter in the obvious hope of buying the Italian title. It worked, with Veron the fulcrum of a Lazio side that was to win the Serie A title, the Italian Cup and the Super-Cup in 2000. Veron was at that time being mentioned as one of the greatest players in the World, and alongside his miraculous passing ability, he was scoring some impressive goals :

But controversy was already following him. There had been talk about the vailidity of his European passport in Italy for some time, and in 2001 a scandal erupted. Veron, feeling that Lazio were not offering him the proper support, moved to Man Utd in July for £28.1 million, a British record fee. His escalating value and the talk of his ability increased expectations at the club, which had won the Premiership in each of the preceding three seasons. Veron slotted into what had been, at its peak, arguably the best midfield in Europe, with Ryan Giggs on the left wing, David Beckham the right, Roy Keane and Paul Scholes in the middle and Nicky Butt as a utility player. Veron was expected to play in the centre with Keane, but the two proved curiously incompatable. Keane was no mere water-carrier in the Simeone mould, but a box-to-box player, who tackled, harried, organised everyone around him and established his own rhythm of simple, short passes and directed and bullied his team all over the pitch. Whereas Keane and Scholes had played together for years and had developed an understanding, Veron and Keane never really got the chance to. Keane's game seemed to cancel out Veron's, making him strangely peripheral in many games, his obvious gifts blunted. Veron also seemed disturbed by the pace and intensity of the Premiership, where he was never given the time he had taken for granted in Italy. After some early promise his performances in England became inconsistent, and his spirit and attitude were questioned. In his first season with United, Arsenal won the League, United exited the Champions League to Bayer Leverkusen, and his status as a great player was brought into doubt.

His salvation seemed to lie in that summers world Cup in Japan and Korea, where Argentina were pre-tournament favourites alongside holders France. This was an Argentina side where Veron was the chief creative force, coach Marcelo Bielsa favouring a European-style pressing game which had seen his squad take the qualifiers in South America by storm. But following the countries recent Economic meltdown, there was a lot of pressure on the players to lift the nation. That job was made more difficult by the group they had been drawn in - this tournaments "Group of Death" alongside England, Sweden and Nigeria. Argentina were to discover that the fast pace that had worked so well in South America was less effective against European teams used to playing at such a pace. They beat Nigeria 1-0 in their first game, but failed to really gel, with Veron quiet and not as dominant as he had been in the qualifiers. He had arrived for the tournament having picked up an injury and struggled for fitness throughout, which was evident in the next game, a 1-0 defeat to England. Though Argentina controlled the majority of the possession, Veron was outplayed by a combination of his United colleagues, Scholes and Butt, with the latter particularly effective at closing down and hassling the Argentine. He was substituted midway through the second half and replaced by Pablo Aimar, a playmaker more in the classic Argentine mould, who, with his quick feet and clever link-up play, offered a much more acute threat in his time on the pitch than Veron had done. Devastated by that defeat to such old rivals, Argentina could only scrape a 1-1 draw with Sweden, and were eliminated from the competition. Many at home blamed Veron.

This was evident when he played in the teams first competitive home match since the World Cup, a South American qualifier against local rivals Chile in Buenos Aires in 2003. The crime of playing so poorly in 2002 was compounded by Veron making his living in England - as banners around the stadium reminded him - and he was booed onto the pitch and throughout the game by his own fans. Soon after, injured yet again, Veron lost his place in the squad. When Jose Pekarman replaced Bielsa as Coach, he made his preference for Riquelme as playmaker plain, and Veron was frozen out. He did not help his case any by feuding with Argentine captain Juan Pablo Sorin, however. The injury that cost him his place in the squad was also to lead to his departure from United. He played better in his second season in England, enjoying a run in the team alongside Phil Neville at the heart of midfield due to injuries to both Keane and Butt. Their twin showing against Arsenal - a gritty 2-0 win when Veron tackled, chased, closed down, and looked as if he had adjusted to the Premiership with ease - was a big turning point in the struggle for the title that season. He had always played better in the Champions League, and this season was no different, as he made and scored goals in the Group stages. However, his injury ruled him out at a crucial late stage in the season when United began a trademark run of victories to come from behind and overtake a flagging Arsenal. This was mostly achieved by the classic Giggs-Keane-Scholes-Beckham midfield, and in th echampions League, Veron returned to fitness too late to help the team overcome Real Madrid at Old Trafford, where they lost on aggregate. He celebrated winning a Premiership medal, but Alex Ferguson had seen that his team played just as well without Veron, and he was sold, against his wishes, to Chelsea for £15 million in the summer.

Chelsea had just been bought by Roman Abramovich and Manager Claudio Rainieri went on something of a spending spree, buying Damian Duff, Joe Cole, Hernan Crespo and Claude Makelele in addition to Veron that summer. Veron started well, scoring a goal in the first day victory over Liverpool, but he missed much of the rest of the season through injury, again returning to be brought on (and played catastrophically out of position, on the wing) in Chelsea's Champions League Semi-final defeat to Monaco. Chelsea fans, suspicious of having signed a player who had seemed to fail so conspicuously in Manchester and preferring Lampard, Cole and Makelele in midfield, already regarded him as a flop, after a single season. Rainieri was sacked and replaced by Jose Mourinho, who loaned Veron to Inter Milan for the next two seasons. Playing again at a pace he liked and in a more sympathetic, latin environment, Veron began to show his qualities once more, helping Inter to Italian Cup victories in 2005 and 2006.

This is a story with something of a happy ending. In 2006, Veron returned to Argentina, to the club of his boyhood and his father, Estudiantes. Now coached by his old friend and midfield minder Diego Simeone, Estudiantes had not won an Argentine championship in 23 years. With a month left in the Argentine Apertura, it looked like they would have to wait. But Boca Juniors kept on dropping points and Estudiantes, with Veron's experience and vision well-served by a young team full of hunger and potential, kept on picking them up. Eventually it came down to a play-off. Boca went 1-0 ahead in the first half, but Estudiantes, encapsulating their season in a single match, emerged victors at 2-1, and won their first championship in 23 years. A few weeks later, Veron was called up to the Argentina squad for the first time in 4 years. New Coach Alfio Basile was ardent in his desire to be an actual working coach for Argentina and not just a selector, and so he called up a squad of domestic-based Argentine players for a training camp. Veron obviously benefitted from this and with Basile declaring his intention to select more of these players in the future, there is a chance that he may play in this summers Copa America in Venezuala. Perhaps his comeback - and redemption, in the eyes of Argentina fans - is still to play itself out. In terms of his career, his major error was in underestimating just how difficult it would be for him in England - he trusted in his talent, and then discovered that it was a talent requiring specific conditions in which to flourish. Those years of failure at what should have been his peak hang over his career, but he is a player with Champions Medals from Italy, England and Argentina on his mantel, not a bad haul by any standards.

Heres a good compilation of what hes capable of, with as many great asists as goals :

Labels:

argentinean football,

boca juniors,

football,

man utd

Friday, December 22, 2006

Mark Hughes

Sometimes you simply cannot avoid football cliches. Sometimes they say it all, so well, that you have to embrace them. Mark Hughes, or Sparky, as Man Utd fans know him, was never a great goalscorer. But he was most definitely a scorer of great goals.

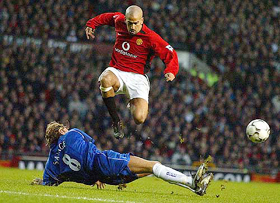

The picture of him above sums it up - he scored a preposterous amount of volleys in his career, among them some astounding, acrobatic scissors kicks, bicycle kicks, and the occasional plain or garden variety volley whilst he was actually facing goal. My first memories of him are for his amazing volleyed goals, one scored for Wales against Spain in a World Cup qualifier (in 1985, I think) where he leapt into the air and scissor-kicked an outrageously high ball into the top corner from the edge of the box:

He saved Man Utd in the 1994 FA Cup final with a volley in the last few minutes:

He also had a propensity for screamers from distance and insanely brave headers. He was my favourite Utd player when I was a little kid, and I was gutted when he was sold to Barcelona in 1986. But that somehow just made it even sweeter when he returned in 1988 and went on to be part of Alex Ferguson's first title - and Double - winning team.

He had joined United straight from school in 1980 and made his debut in 1983. That United team, managed by Ron Atkinson, was a complex beast, full of class and talent with the likes of Arnold Muhren, Paul McGrath and Gordon Strachan, but also a team of big, scary warriors - the likes of Bryan Robson and Kevin Moran. Perhaps their scariest pairing was up-front : Mark Hughes and Norman Whiteside. Both big, physical players, both young and technically gifted, both fond of a tackle in a typically bruising celtic manner. Hughes' strengths were obvious even then - he had phenomenal upper-body strength, and his ability to hold up the ball was better than any other forward of his generation. Tough enough to handle any rough treatment from defenders, he was aggressive enough to give it back. Throughout his career, when I read interviews with Centre-halves from various clubs they would name him as their most difficult opponent. Not because he would tear past them with the ball glued to his toe then rifle it into the top corner - though on a good day, he could do that too - but because he would chase them down, tackle them as hard as they tackled him, win more than his share of headers against them and generally never give them any time to relax.

Fans loved him for that, but his eye for a spectacular goal didn't hurt. He scored 37 in his first 89 games before the move to Barcelona, in which time Utd won the FA Cup, in 1985, the same year in which Hughes was voted PFA Young Player of the Year. He failed at Barcelona, his form deserting him, perhaps due to the more patient, technical nature of the Spanish game. Hughes physical gifts and bombastic workrate did not work as well in the Nou Camp as his new teammate Gary Lineker's sneakiness and perfectly-timed runs into the box. It took a loan move to Bayern Munich in 1987-88 for his form and self-belief to return. Alex Ferguson then brought him back to Utd for a club record £1.8 million, a bargain when you consider that he went on to score 82 goals in 256 appearances, win the FA Cup twice more, the League Cup once, and the League itself twice. Most satisfying for him was probably the Cup Winners Cup Final in 1991, when he scored both goals against his old club Barcelona, the second, the winner, a crushing drive from a seemingly impossible angle.

He also won PFA Players Player of the year twice in this period, in 1989 and 1991, and it is the high regard in which he was held by his peers that perhaps speaks most eloquently about what an honest, hard-working player he was. That first title-winning Utd side of Ferguson's was built almost entirely on strong personalities - men with backbone and fighting spirit. Schmeichel, Bruce, Pallister, Robson, Ince, Cantona and Hughes were a fearsome line of footballers, willing to battle for results when the flair they usually deployed wasn't working. Hughes was Cantona's favourite strike partner, willing to do the dirty work and let Eric strut his stuff, but also capable of turning a game on his own with one of those spectacular leaps or diving headers. His distribution was always astute, and he and Cantona seemed capable of reading each others runs and movement perfectly. With Brian McClair as their third striker, that United side was able to outscore most opponents.

Hughes second departure from United, in 1995, was due to his age. He was 32 at the time, and Ferguson wanted to build a new, younger United squad, so he was sold to Chelsea in a clear-out that also included the sale of both Paul Ince and Andrei Kanchelskis. Hughes enjoyed something of a renaissance at Chelsea, scoring 25 goals in 95 games between 1995 and 2000, and helping the club win the FA Cup in 1997 and the Cup Winners Cup in 1998. He then spent a few years wandering from Southampton to Everton to Blackburn, sometimes using his physical presence and experience in central midfield, from where he was probably the key player in the 2002 League Cup final as Blackburn beat Tottenham 2-1.

The newfound maturity and leadership he displayed on the pitch may have grown out of his new role as a manager, as he had taken over as Wales Coach in 1999. He rejuvenated the Welsh squad and brought them closer to a major tournament than at any time since 1986 - when they had narrowly lost out to Scotland - by securing a play-off spot against Russia, which they lost, 1-0 over two legs. Hughes then moved to Blackburn as manager, where his relative success has positioned him firmly for the job of coach at his old stomping ground whenever Alex Ferguson decides he has had enough.

However successful he may be as Coach, his attitude and skill as a player is unforgettable :

Labels:

barcelona,

football,

man utd,

mullets,

welsh football

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)